Difference between revisions of "User:Tohline/SSC/UniformDensity"

(→Setup: Change link for structure of uniform-density sphere) |

|||

| (35 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- __FORCETOC__ will force the creation of a Table of Contents --> | <!-- __FORCETOC__ will force the creation of a Table of Contents --> | ||

<!-- __NOTOC__ will force TOC off --> | <!-- __NOTOC__ will force TOC off --> | ||

=The Stability of Uniform-Density Spheres= | |||

{{LSU_HBook_header}} | {{LSU_HBook_header}} | ||

As far as we have been able to determine, [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S T. E. Sterne (1937, MNRAS, 97, 582)] was the first to use linearized perturbation techniques and, specifically, the [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#2ndOrderODE|''Adiabatic Wave Equation'']], to thoroughly analyze the stability of uniform-density, self-gravitating spheres. While uniform-density configurations present an overly simplified description of real stars, [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne's (1937)] stability analysis is an important one because it presents a complete spectrum of radial pulsation eigenvectors — eigenfrequencies ''plus'' the corresponding eigenfunctions — as closed-form analytic expressions. Such analytic solutions are quite rare in the context of studies of the structure, stability, and dynamics of self-gravitating fluids. | |||

[[ | |||

As has been explained in an [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#The_Eigenvalue_Problem|accompanying introductory discussion]], this type of stability analysis requires the solution of an eigenvalue problem. Here we begin by re-presenting the governing 2<sup>nd</sup>-order ODE (the [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#2ndOrderODE|''Adiabatic Wave Equation'']]) as it was derived in the accompanying introductory discussion, along with the specification of two customarily used boundary conditions; and we review the properties of the equilibrium configuration — also derived in a [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/UniformDensity#Isolated_Uniform-Density_Sphere|separate discussion]] — that are relevant to this stability analysis. Interleaved with this presentation, we also show the governing wave equation as it was derived by [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne (1937)] — and a table that translates from Sterne's notation to ours — along with his corresponding review of the properties of the unperturbed equilibrium configuration. Finally, we present [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne's (1937)] solution to this eigenvalue problem and discuss the properties of his derived radial pulsation eigenvectors. | |||

==The Eigenvalue Problem== | ==The Eigenvalue Problem== | ||

===Our Approach=== | |||

As has been derived in [ | As has been derived in [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#Eigen_Value_Problem|an accompanying discussion]], the second-order ODE that defines the relevant Eigenvalue problem is, | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

| Line 37: | Line 36: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== | The two [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#Boundary_Conditions|boundary conditions]] are, | ||

===Setup=== | <div align="center"> | ||

From our derived [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/ | <math>~\frac{dx}{d\chi_0} = 0</math> at <math>~\chi_0 = 0 \, ;</math> | ||

</div> | |||

and, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~ \frac{d\ln x}{d\chi_0}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{1}{\gamma_g} \biggl( 4 - 3\gamma_g + \frac{\omega^2 R^3}{GM_\mathrm{tot}}\biggr) </math> at <math>~\chi_0 = 1 \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

===The Approach Taken by Sterne (1937)=== | |||

[http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S T. E. Sterne (1937)] begins his analysis by deriving the | |||

<div align="center" id="2ndOrderODE"> | |||

<font color="#770000">'''Adiabatic Wave''' (or ''Radial Pulsation'') '''Equation'''</font><br /> | |||

{{User:Tohline/Math/EQ_RadialPulsation01}} | |||

</div> | |||

in a manner explicitly designed to reproduce [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#Eddington_.281926.29|Eddington's ''pulsation equation'']] — it appears as equation (1.8) in Sterne's paper — and, along with it, the [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#Ensure_Finite-Amplitude_Fluctuations|surface boundary condition]], | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right" > | |||

<math>~ r_0 \frac{d\ln x}{dr_0}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{1}{\gamma_g} \biggl( 4 - 3\gamma_g + \frac{\omega^2 R^3}{GM_\mathrm{tot}}\biggr) </math> at <math>~r_0 = R \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

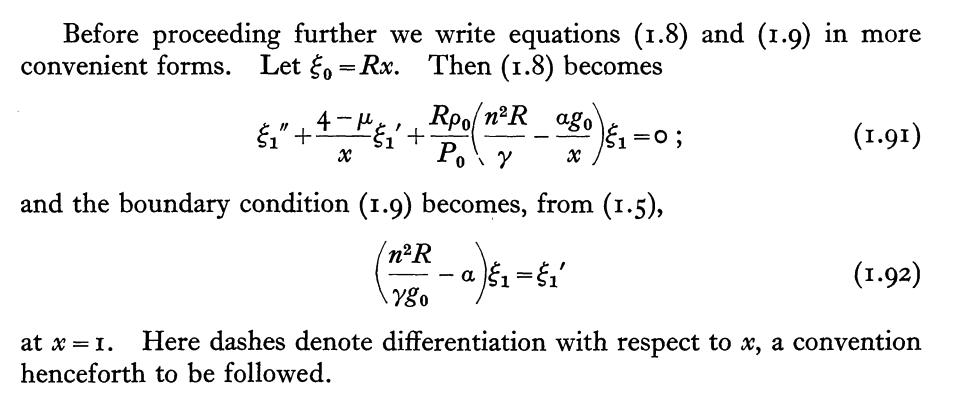

which appears in Sterne's paper as equation (1.9). Then, as shown in the following paragraph extracted directly from his paper, [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne (1937)] rewrites both of these expressions in, what he considers to be, "more convenient forms." | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="2" cellpadding="5"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<th align="center" colspan="1"> | |||

Paragraph extracted from [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S T. E. Sterne (1937)]<p></p> | |||

"''Modes of Radial Oscillation''"<p></p> | |||

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 97, pp. 582 - © [https://www.ras.org.uk/ Royal Astronomical Society] | |||

</th> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td colspan="1"> | |||

[[File:Sterne1937B.png|600px|center|Sterne (1937)]] | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr><td align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" width="75%" cellpadding="4"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" colspan="3"> | |||

<font size="+1">'''Notation:'''</font> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<th align="center" width="40%"><font size="+1">Sterne's</font><p></p> | |||

----</th> | |||

<td width="20%"> </td> | |||

<th align="center"><font size="+1">Ours</font><p></p> | |||

----</th> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" width="40%"><math>~\xi_0 = Rx</math></td> | |||

<td> </td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~r_0</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" width="40%"><math>~\xi_1</math></td> | |||

<td> </td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~x</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" width="40%"><math>~n^2</math></td> | |||

<td> </td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~\omega^2</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" width="40%"><math>~\alpha</math></td> | |||

<td> </td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~3-4/\gamma_g</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" width="40%"><math>~\mu</math></td> | |||

<td> </td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~g_0 \rho_0 r_0/P_0</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center" width="40%"><math>~g_0 R^2</math></td> | |||

<td> </td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~GM_\mathrm{tot}</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</td></tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

==Properties of the Equilibrium Configuration== | |||

=== Our Setup=== | |||

From our derived [[User:Tohline/SSC/Structure/Polytropes#n_.3D_0_Polytrope|structure of a uniform-density sphere]], in terms of the configuration's radius <math>R</math> and mass <math>M</math>, the central pressure and density are, respectively, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math>P_c = \frac{3G}{8\pi}\biggl( \frac{M^2}{R^4} \biggr) </math> , | <math>P_c = \frac{3G}{8\pi}\biggl( \frac{M^2}{R^4} \biggr) </math> , | ||

| Line 80: | Line 196: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

So our desired | So our desired eigenfunctions and eigenvalues will be solutions to the following ODE: | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 86: | Line 202: | ||

</math><br /> | </math><br /> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

===Setup as Presented by Sterne (1937)=== | |||

In §2 of his paper, Sterne (1937) details the structural properties of an equilibrium, uniform-density sphere as follows. (Text taken verbatim from Sterne's paper are presented here in green.) Given that <font color="green">the undisturbed density is constant and equal to the mean density</font>, <math>~\bar\rho</math>, the <font color="green">mass within any radius is</font>, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>M_r = \biggl( \frac{4\pi}{3} \biggr) \bar\rho \xi_0^3 \, ;</math> | |||

</div> | |||

<font color="green">the undisturbed values of gravity and the pressure are</font>, respectively, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>g_0 \equiv \frac{GM_r}{\xi_0^2} = \biggl( \frac{4\pi}{3} \biggr) G\bar\rho R x \, </math> | |||

</div> | |||

and | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>P_0 = \biggl( \frac{2\pi}{3} \biggr) G R^2 \bar\rho^2(1 - x^2) \, ;</math> | |||

</div> | |||

and the quantity, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>\mu \equiv \frac{g_0 \bar\rho \xi_0}{P_0} = \frac{2x^2}{(1-x^2)} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Hence, for this particular equilibrium model, Sterne's derived wave equation — his equation (1.91), as displayed above — becomes, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~0</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^{ ' ' } + \biggl[\frac{4-\mu}{x} \biggr]\xi_1^' + \frac{R\bar\rho}{P_0} \biggl( \frac{n^2 R}{\gamma} - \frac{\alpha g_0}{x} \biggr) \xi_1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 -\frac{2x^2}{(1-x^2)} \biggr]\xi_1^' + | |||

\frac{3}{2\pi G R \bar\rho (1 - x^2)}\biggl[ \frac{n^2 R}{\gamma} - \biggl( \frac{4\pi}{3} \biggr) \alpha G\bar\rho R \biggr] \xi_1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4(1-x^2) - 2x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \biggl[ \frac{3n^2 }{2\pi \gamma G \bar\rho} - 2 \alpha \biggr] \xi_1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

where, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\mathfrak{F} \equiv \frac{3n^2 }{2\pi \gamma G \bar\rho} - 2 \alpha \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Note that, once the value of the parameter, <math>~\mathfrak{F}</math>, has been determined for a given eigenvector, the square of the eigenfrequency will also be known via the inversion of this last expression. Specifically, in terms of <math>~\mathfrak{F}</math>, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~n^2</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{2\pi \gamma G \bar\rho}{3} \biggl[ \mathfrak{F} + 2 \biggl(3-\frac{4}{\gamma}\biggr)\biggr]</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~~ \frac{n^2}{4\pi G \bar\rho}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr)\gamma -\frac{4}{3} \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

As a reminder, in these terms the inner boundary condition is | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^'\biggr|_{x = 0} = 0 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

And the outer boundary condition becomes, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^'</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1 \biggl( \frac{n^2 R}{\gamma g_0} - \alpha \biggr)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1 \biggl[ \frac{3}{x}\biggl( \frac{n^2 }{4\pi \gamma G\bar\rho } \biggr) - 3 + \frac{4}{\gamma} \biggr]</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~3\xi_1 \biggl\{ \frac{1}{x}\biggl[ \biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr) -\frac{4}{3\gamma} \biggr] - 1 + \frac{4}{3\gamma} \biggr\}</math> at | |||

<math>~x = 1 \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~~~\biggl[ \xi_1^' - \frac{\mathfrak{F} \xi_1}{2} \biggr]_{x=1}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~0 \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

<!-- OMIT NEXT TEXT | |||

==Analytic Solution== | |||

===First few lowest-order modes=== | ===First few lowest-order modes=== | ||

| Line 153: | Line 440: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

END OMISSION --> | |||

==Sterne's General Solution== | |||

===Sterne's Presentation=== | |||

In what follows, as before, text presented in a green font has been taken verbatim from the paper by [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne (1937)]. Sterne begins by writing the unknown eigenfunction as a power series expanded about the origin, specifically, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\sum\limits_{0}^{\infty} a_k x^k \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

with, <math>~a_0 = 1</math>. <font color="green">It is found by substitution that the terms in odd powers of <math>~x</math> vanish, and that the coefficients of the even terms satisfy the recurrence formula</font>, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~a_{k+2}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~a_k \cdot \frac{k^2 + 5k - \mathfrak{F}}{(k+2)(k+5)} \, .</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

The wave equation and attending boundary conditions will all <font color="green">be satisfied if we choose <math>\mathfrak{F}</math> so as to make the series solution terminate with some term, say the <math>~2 j^\mathrm{th}</math> where <math>~j</math> is zero or any positive integer. This it will do</font> [via the above recurrence relation] if, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\mathfrak{F} = 2j(2j+5) \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

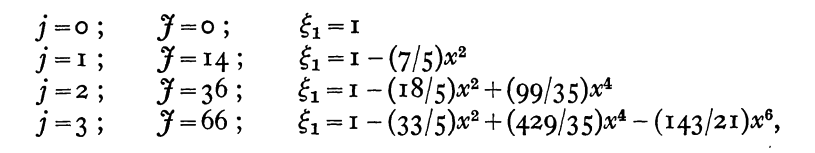

The first few solutions are displayed in the following boxed-in image that has been extracted directly from §2 (p. 587) of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne (1937)]; to the right of Sterne's table, we have added a column that expressly records the value of the square of the normalized eigenfrequency that corresponds to each of Sterne's solutions. | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="2" cellpadding="5"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<th align="center" colspan="1"> | |||

Table extracted from [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S T. E. Sterne (1937)]<p></p> | |||

"''Modes of Radial Oscillation''"<p></p> | |||

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 97, pp. 582 - © [https://www.ras.org.uk/ Royal Astronomical Society] | |||

</th> | |||

<th align="center" colspan="1"> | |||

<math>~\frac{n^2}{4\pi G \bar\rho}</math> | |||

</th> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td colspan="1" rowspan="4"> | |||

[[File:Sterne1937SolutionTable1.png|600px|center|Sterne (1937)]] | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~\gamma - 4/3</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~2(5\gamma - 2)/3</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~7\gamma - 4/3</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="center"><math>~12\gamma - 4/3</math></td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

===Validity Check=== | |||

Let's explicitly demonstrate that the first few eigenvectors derived by Sterne actually satisfy the governing adiabatic wave equation and the two boundary conditions. | |||

====Mode j = 0:==== | |||

In this case, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1 = 1</math> | |||

and | |||

<math>~\mathfrak{F} = 0 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Hence, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^' \equiv \frac{d\xi_1}{dx} = 0 \, ;</math> | |||

and | |||

<math>\xi_1^{' '} \equiv \frac{d^2\xi_1}{dx^2} = 0 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

So, the adiabatic wave equation gives, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~(1-x^2) (0) + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr](0) + (0)(1) \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

which properly sums to zero. Next, because <math>~\xi_1^' = 0</math> everywhere, we know that it is zero at the center of the configuration, which satisfies the inner boundary condition. But, via the outer boundary condition, this also means that the product, <math>~(\tfrac{1}{2} \mathfrak{F} \xi_1)</math> should be zero; which it is, because <math>~\mathfrak{F} = 0</math> for this mode. | |||

====Mode j = 1:==== | |||

In this case, according to [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne (1937)], | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1 = 1 - \frac{7}{5} x^2 \, ,</math> | |||

and | |||

<math>~\mathfrak{F} = 14 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

Hence, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^' = - \frac{14}{5} x \, ;</math> | |||

and | |||

<math>\xi_1^{' '} = - \frac{14}{5} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

So, the adiabatic wave equation gives, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~- \frac{14}{5}(1-x^2) - \frac{14}{5}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr] + 14 \biggl( 1 - \frac{7}{5} x^2 \biggr) </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{14}{5}\biggl[- (1-x^2) - (4 - 6x^2 ) +5 - 7 x^2 \biggr] \, , </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

which properly sums to zero for all <math>~x</math>. Next, it is clear that the inner boundary condition is satisfied because, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi_1^'\biggr|_{x = 0} = - \frac{14}{5} (0)= 0 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

And the expression for the outer boundary condition gives, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ \xi_1^' - \frac{\mathfrak{F} \xi_1}{2} \biggr]_{x=1}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ -\biggl(\frac{14}{5} \biggr) x - 7 \biggl( 1 - \frac{7}{5}x^2 \biggr) \biggr]_{x=1} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

== | <tr> | ||

=== | <td align="right"> | ||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ -\biggl(\frac{14}{5} \biggr) - 7 \biggl( 1 - \frac{7}{5} \biggr) \biggr] \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

which also properly sums to zero. | |||

====Mode j = 2:==== | |||

In this case, according to [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1937MNRAS..97..582S Sterne (1937)], | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math>~\xi_1 = 1 - \frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5} x^2 + \frac{3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 \, ,</math> | ||

and | |||

<math>~\mathfrak{F} = 2^2 \cdot 3^2 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

Hence, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math>\ | <math>~\xi_1^' = - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} x + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^3 \, ;</math> | ||

and | |||

<math>\xi_1^{' '} = - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^2 \, .</math> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

So, the adiabatic wave equation gives, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

(1-x^2) \biggl[- \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^2 \biggr] | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

+ 2\biggl[2 - 3x^2 \biggr]\biggl[- \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^2\biggr] | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

+ 2^2 \cdot 3^2 \biggl[ 1 - \frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5} x^2 + \frac{3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 \biggr] | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

- \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \biggl[\frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} | |||

+ \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} \biggr] x^2 - \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

- \frac{2^4\cdot 3^2}{5} +\biggl[ \frac{2^4 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} | |||

+ \frac{2^3\cdot 3^3}{5} \biggr]x^2 - \frac{2^3 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

+ 2^2 \cdot 3^2 - \frac{2^3\cdot 3^4}{5} x^2 + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^4 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

\frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5}\biggl[ -1 -4 + 5\biggr] + \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5\cdot 7}\biggl[33 + 7 + 44 + 42 - 2\cdot 3^2 \cdot 7\biggr] x^2 | |||

+ \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} \biggl[ 3 - 2 - 1\biggr] x^4 \, , | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

which properly sums to zero for all <math>~x</math>. Next, it is clear that the inner boundary condition is satisfied because, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math>~\xi_1^'\biggr|_{x = 0} = - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} (0) + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} (0) = 0 \, .</math> | ||

\ | |||

\ | |||

\ | |||

</math | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

And the expression for the outer boundary condition gives, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | ||

</math>< | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ \xi_1^' - \frac{\mathfrak{F} \xi_1}{2} \biggr]_{x=1}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} x + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^3 | |||

- 2\cdot 3^2 \biggl( 1 - \frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5} x^2 + \frac{3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 \biggr) \biggr]_{x=1} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5\cdot 7}\biggl[ -14 + 22 - \biggl( 35 - 126 + 99 \biggr) \biggr] \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

which also properly sums to zero. | |||

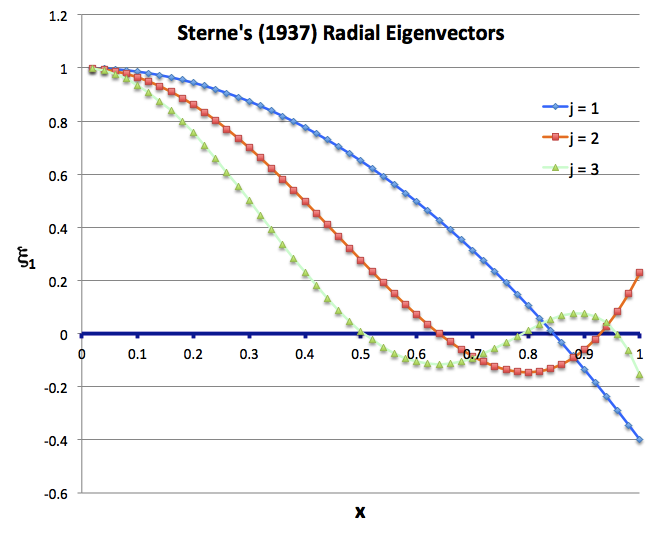

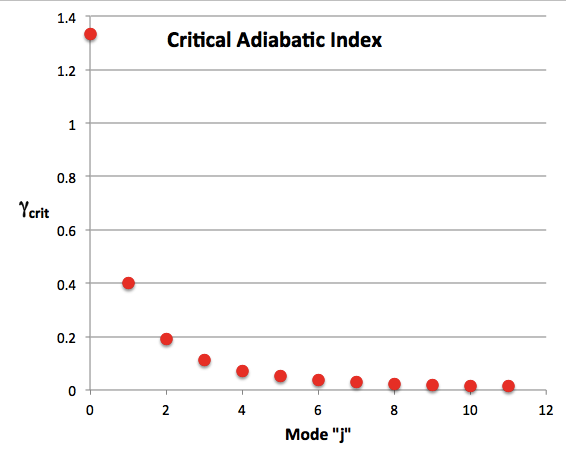

===Properties of Eigenfunction Solutions=== | |||

<table border="1" cellpadding="2" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td colspan="1" align="center"> | |||

[[File:Sterne1937SolutionPlot1.png|350px|center|Sterne (1937)]] | |||

</td> | |||

<td colspan="1" align="center"> | |||

[[File:Sterne1937CritGamma1.png|350px|center|Sterne (1937)]] | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

==Stability== | |||

The | The [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#2ndOrderODE|Adiabatic Wave Equation]] that defines this [[User:Tohline/SSC/Perturbations#The_Eigenvalue_Problem|eigenvalue problem]] has been derived from the fundamental set of nonlinear [[User:Tohline/PGE#Principal_Governing_Equations|Principal Governing Equations]] by assuming that, for example, the radial position, <math>~r(m,t)</math>, at any time, <math>~t</math>, and of each mass shell throughout our spherical configuration can be described by the expression, | ||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~r(m,t) = r_0(m) [ 1 + x(m) e^{i\omega t} ] \, ,</math> | |||

</div> | |||

where, the fractional displacement, <math>~|x| \ll 1</math>. Switching to Sterne's variable notation, this should be written as, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\xi(x,t) = \xi_0(x) [ 1 + A\xi_1(x) e^{i n t} ] \, ,</math> | |||

</div> | |||

with the presumption that the coefficient, <math>~|A| \ll 1</math>, and the understanding that, in Sterne's presentation, the variable, <math>~x</math>, is used to identify individual mass shells. Specifically, given <math>~R</math> and <math>~\bar\rho</math>, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math>\frac{\ | <math>~m \equiv M_r = \frac{4}{3}\pi \xi_0^3 \bar\rho = \frac{4}{3}\pi (R x)^3 \bar\rho </math> | ||

<math>~\Rightarrow</math> | |||

<math>~x = \biggl( \frac{3m}{4\pi R^3 \bar\rho} \biggr)^{1/3} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

Sterne's [[User:Tohline/SSC/UniformDensity#Sterne.27s_General_Solution|general solution of this eigenvalue problem]] describes mathematically how a self-gravitating, uniform-density configuration will vibrate if perturbed away from its equilibrium state; the oscillatory behavior associated with each pure radial mode, <math>~j</math> — among an infinite number of possible modes — is fully defined by the polynomial expression for the eigenvector, <math>~\xi_1(x)</math>, and the corresponding value of the square of the eigenfrequency, <math>~n^2</math>. | |||

If, for any mode, <math>~j</math>, the ''square'' of the derived eigenfrequency, <math>~n^2</math>, is positive, then the eigenfrequency itself will be a real number — specifically, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~n = \pm \sqrt{|n^2|} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

As a result, the radial location of every mass shell will vary sinusoidally in time according to the expression, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\frac{\xi(x,t)}{\xi_0} - 1 \propto e^{\pm i \sqrt{|n^2|} t} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

If, on the other hand, <math>~n^2</math>, is negative, then the eigenfrequency will be an imaginary number — specifically, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~n = \pm i \sqrt{|n^2|} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

As a result, the radial location of every mass shell will grow (or damp) exponentially in time according to the expression, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<math>~\frac{\xi(x,t)}{\xi_0} - 1 \propto e^{\pm \sqrt{|n^2|} t} \, .</math> | |||

</div> | |||

This latter condition is the mark of a dynamically unstable system. It is in this manner that the solution to an eigenvalue problem can provide critical information regarding the relative stability of equilibrium configurations. | |||

For any given mode number, <math>~j</math>, then, the critical configuration separating stable from unstable systems occurs when the dimensionless eigenfrequency is zero. Therefore, the critical state occurs when, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math>\frac{ | <table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | ||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~0 = \frac{n_\mathrm{crit}^2}{4\pi G \bar\rho}</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr)\gamma_\mathrm{crit} -\frac{4}{3} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~~ \gamma_\mathrm{crit}(j)</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{4}{3}\biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr)^{-1} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{4}{3}\biggl[1 + \frac{2j(2j+5)}{6} \biggr]^{-1} </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

| |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{4}{3 + j(2j+5)} \, . </math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

The plot titled, "Critical Adiabatic Index," that is [[User:Tohline/SSC/UniformDensity#Properties_of_Eigenfunction_Solutions| presented above]] shows graphically how <math>~\gamma_\mathrm{crit}</math> varies with mode number over the range of mode numbers, <math>~0 \le j \le 11</math>. All modes are stable as long as <math>~\gamma > 4/3</math>. As the adiabatic index is decreased below this value, the lowest order mode, <math>~j = 0</math>, becomes unstable, first; then successively higher order modes become unstable at smaller and smaller values of the index. A very similar explanation and enunciation of Sterne's derived results regarding the stability of uniform-density spheres appears on p. 338 of the paper by [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1946ApJ...104..333L P. Ledoux (1946)] titled, ''On the Dynamical Stability of Stars''. The relevant paragraph from Ledoux's paper is reprinted as a boxed-in digital image in the following table: | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

< | <table border="2" cellpadding="5" width="80%"> | ||

<tr> | |||

\ | <th align="center" colspan="1"> | ||

</ | Paragraph extracted<sup>†</sup> from p. 338 of [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1946ApJ...104..333L P. Ledoux (1946)]<p></p> | ||

"''On the Dynamical Stability of Stars''"<p></p> | |||

The Astrophysical Journal, vol. 104, pp. 333 - 346 © [http://aas.org/about/policies/copyright American Astronomical Society] | |||

</th> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td colspan="1" rowspan="1"> | |||

[[File:Ledoux1946OnSterne01.png|700px|center|Ledoux (1946)]] | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<sup>†</sup>Our function, <math>~\gamma_\mathrm{crit}(j)</math>, is effectively the expression to which Ledoux is referring when he says, "… directly verify from equation (19) …" | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

==Numerical Integration== | |||

In order to gain a more complete understanding of this type of modal analysis, let's attempt to obtain various eigenvectors by numerically integrating the governing LAWE from the center of the system, outward to the surface. This will be done in a manner similar to our [[User:Tohline/Appendix/Ramblings/NumericallyDeterminedEigenvectors#Numerically_Determined_Eigenvectors_of_a_Zero-Zero_Bipolytrope|numerical study of radial oscillations in zero-zero bipolytropes]]. Following our [[User:Tohline/SSC/UniformDensity#Setup_as_Presented_by_Sterne_.281937.29|above review of Sterne's presentation]], the relevant LAWE is, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~x(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } </math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~- (4 - 6x^2 )\xi_1^' - x \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 \, ,</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

where, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <math>~\mathfrak{F} \equiv \frac{\sigma_c^2}{\gamma} - 2 \alpha = \frac{\sigma_c^2 + 8}{\gamma} - 6\, ,</math> | ||

\ | and, | ||

</math | <math>~\sigma_c^2 \equiv \frac{3n^2 }{2\pi G \rho_c} \, .</math> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Following precisely the same logic as has been laid out in our [[User:Tohline/Appendix/Ramblings/NumericallyDeterminedEigenvectors#Integrating_Outward_Through_the_Core|separate discussion]], if we set the central value of the eigenfunction to <math>~\xi_0</math>, then the eigenfunction's value at the first zone (distance <math>~\Delta</math>) away from the center will be, | |||

<div align="center"> | |||

<table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | |||

<tr> | |||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

\xi_+ | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~=</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\biggl[ 1 - \frac{\Delta^2 \mathfrak{F}}{2} \biggr] \xi_0 \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | |||

While, for each successive coordinate location, <math>~a = x</math>, in the range, <math>~0 < x < 1</math>, we will use the general expression, namely, | |||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<math> | <table border="0" cellpadding="5" align="center"> | ||

\ | |||

</math>< | <tr> | ||

<td align="right"> | |||

<math>~ | |||

\Rightarrow~~~\xi_+ | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="center"> | |||

<math>~\approx</math> | |||

</td> | |||

<td align="left"> | |||

<math>~\frac{[4a (1 - a^2) - 2\Delta^2 a \mathfrak{F} ]\xi_a | |||

+ [ \Delta( 4 - 6a^2 ) - 2a (1 - a^2)] \xi_- }{[2a (1 - a^2) + \Delta( 4 - 6a^2 ) ] } \, . | |||

</math> | |||

</td> | |||

</tr> | |||

</table> | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

{{LSU_HBook_footer}} | {{LSU_HBook_footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:07, 15 February 2017

The Stability of Uniform-Density Spheres

|

|---|

| | Tiled Menu | Tables of Content | Banner Video | Tohline Home Page | |

As far as we have been able to determine, T. E. Sterne (1937, MNRAS, 97, 582) was the first to use linearized perturbation techniques and, specifically, the Adiabatic Wave Equation, to thoroughly analyze the stability of uniform-density, self-gravitating spheres. While uniform-density configurations present an overly simplified description of real stars, Sterne's (1937) stability analysis is an important one because it presents a complete spectrum of radial pulsation eigenvectors — eigenfrequencies plus the corresponding eigenfunctions — as closed-form analytic expressions. Such analytic solutions are quite rare in the context of studies of the structure, stability, and dynamics of self-gravitating fluids.

As has been explained in an accompanying introductory discussion, this type of stability analysis requires the solution of an eigenvalue problem. Here we begin by re-presenting the governing 2nd-order ODE (the Adiabatic Wave Equation) as it was derived in the accompanying introductory discussion, along with the specification of two customarily used boundary conditions; and we review the properties of the equilibrium configuration — also derived in a separate discussion — that are relevant to this stability analysis. Interleaved with this presentation, we also show the governing wave equation as it was derived by Sterne (1937) — and a table that translates from Sterne's notation to ours — along with his corresponding review of the properties of the unperturbed equilibrium configuration. Finally, we present Sterne's (1937) solution to this eigenvalue problem and discuss the properties of his derived radial pulsation eigenvectors.

The Eigenvalue Problem

Our Approach

As has been derived in an accompanying discussion, the second-order ODE that defines the relevant Eigenvalue problem is,

<math>

\frac{d^2x}{d\chi_0^2} + \biggl[\frac{4}{\chi_0} - \biggl(\frac{\rho_0}{\rho_c}\biggr) \biggl(\frac{P_0}{P_c}\biggr)^{-1} \biggl(\frac{g_0}{g_\mathrm{SSC}}\biggr) \biggr] \frac{dx}{d\chi_0} + \biggl(\frac{\rho_0}{\rho_c}\biggr) \biggl(\frac{P_0}{P_c}\biggr)^{-1} \biggl(\frac{1}{\gamma_\mathrm{g}} \biggr)\biggl[\tau_\mathrm{SSC}^2 \omega^2 + (4 - 3\gamma_\mathrm{g})\biggl(\frac{g_0}{g_\mathrm{SSC}}\biggr) \frac{1}{\chi_0} \biggr] x = 0 .

</math>

where the dimensionless radius,

<math>

\chi_0 \equiv \frac{r_0}{R} ,

</math>

the characteristic time for dynamical oscillations in spherically symmetric configurations (SSC) is,

<math>

\tau_\mathrm{SSC} \equiv \biggl[ \frac{R^2 \rho_c}{P_c} \biggr]^{1/2} ,

</math>

and the characteristic gravitational acceleration is,

<math>

g_\mathrm{SSC} \equiv \frac{P_c}{R \rho_c} .

</math>

The two boundary conditions are,

<math>~\frac{dx}{d\chi_0} = 0</math> at <math>~\chi_0 = 0 \, ;</math>

and,

|

<math>~ \frac{d\ln x}{d\chi_0}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{1}{\gamma_g} \biggl( 4 - 3\gamma_g + \frac{\omega^2 R^3}{GM_\mathrm{tot}}\biggr) </math> at <math>~\chi_0 = 1 \, .</math> |

The Approach Taken by Sterne (1937)

T. E. Sterne (1937) begins his analysis by deriving the

Adiabatic Wave (or Radial Pulsation) Equation

|

<math>~ \frac{d^2x}{dr_0^2} + \biggl[\frac{4}{r_0} - \biggl(\frac{g_0 \rho_0}{P_0}\biggr) \biggr] \frac{dx}{dr_0} + \biggl(\frac{\rho_0}{\gamma_\mathrm{g} P_0} \biggr)\biggl[\omega^2 + (4 - 3\gamma_\mathrm{g})\frac{g_0}{r_0} \biggr] x = 0 </math> |

in a manner explicitly designed to reproduce Eddington's pulsation equation — it appears as equation (1.8) in Sterne's paper — and, along with it, the surface boundary condition,

|

<math>~ r_0 \frac{d\ln x}{dr_0}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{1}{\gamma_g} \biggl( 4 - 3\gamma_g + \frac{\omega^2 R^3}{GM_\mathrm{tot}}\biggr) </math> at <math>~r_0 = R \, ,</math> |

which appears in Sterne's paper as equation (1.9). Then, as shown in the following paragraph extracted directly from his paper, Sterne (1937) rewrites both of these expressions in, what he considers to be, "more convenient forms."

|

Paragraph extracted from T. E. Sterne (1937)

"Modes of Radial Oscillation"

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 97, pp. 582 - © Royal Astronomical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Properties of the Equilibrium Configuration

Our Setup

From our derived structure of a uniform-density sphere, in terms of the configuration's radius <math>R</math> and mass <math>M</math>, the central pressure and density are, respectively,

<math>P_c = \frac{3G}{8\pi}\biggl( \frac{M^2}{R^4} \biggr) </math> ,

and

<math>\rho_c = \frac{3M}{4\pi R^3} </math> .

Hence the characteristic time and acceleration are, respectively,

<math>

\tau_\mathrm{SSC} = \biggl[ \frac{R^2 \rho_c}{P_c} \biggr]^{1/2} =

\biggl[ \frac{2R^3 }{GM} \biggr]^{1/2} =

\biggl[ \frac{3}{2\pi G\rho_c} \biggr]^{1/2},

</math>

and,

<math>

g_\mathrm{SSC} = \frac{P_c}{R \rho_c} = \biggl( \frac{GM}{2R^2} \biggr) .

</math>

The required functions are,

- Density:

<math>\frac{\rho_0(r_0)}{\rho_c} = 1 </math> ;

- Pressure:

<math>\frac{P_0(r_0)}{P_c} = 1 - \chi_0^2 </math> ;

- Gravitational acceleration:

<math>

\frac{g_0(r_0)}{g_\mathrm{SSC}} = 2\chi_0 .

</math>

So our desired eigenfunctions and eigenvalues will be solutions to the following ODE:

<math>

\frac{1}{(1 - \chi_0^2)} \biggl\{ (1 - \chi_0^2) \frac{d^2x}{d\chi_0^2} + \frac{4}{\chi_0}\biggl[1 - \frac{3}{2}\chi_0^2 \biggr] \frac{dx}{d\chi_0} + \frac{1}{\gamma_\mathrm{g}} \biggl[\tau_\mathrm{SSC}^2 \omega^2 + 2 (4 - 3\gamma_\mathrm{g}) \biggr] x \biggr\} = 0 .

</math>

Setup as Presented by Sterne (1937)

In §2 of his paper, Sterne (1937) details the structural properties of an equilibrium, uniform-density sphere as follows. (Text taken verbatim from Sterne's paper are presented here in green.) Given that the undisturbed density is constant and equal to the mean density, <math>~\bar\rho</math>, the mass within any radius is,

<math>M_r = \biggl( \frac{4\pi}{3} \biggr) \bar\rho \xi_0^3 \, ;</math>

the undisturbed values of gravity and the pressure are, respectively,

<math>g_0 \equiv \frac{GM_r}{\xi_0^2} = \biggl( \frac{4\pi}{3} \biggr) G\bar\rho R x \, </math>

and

<math>P_0 = \biggl( \frac{2\pi}{3} \biggr) G R^2 \bar\rho^2(1 - x^2) \, ;</math>

and the quantity,

<math>\mu \equiv \frac{g_0 \bar\rho \xi_0}{P_0} = \frac{2x^2}{(1-x^2)} \, .</math>

Hence, for this particular equilibrium model, Sterne's derived wave equation — his equation (1.91), as displayed above — becomes,

|

<math>~0</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\xi_1^{ ' ' } + \biggl[\frac{4-\mu}{x} \biggr]\xi_1^' + \frac{R\bar\rho}{P_0} \biggl( \frac{n^2 R}{\gamma} - \frac{\alpha g_0}{x} \biggr) \xi_1</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 -\frac{2x^2}{(1-x^2)} \biggr]\xi_1^' + \frac{3}{2\pi G R \bar\rho (1 - x^2)}\biggl[ \frac{n^2 R}{\gamma} - \biggl( \frac{4\pi}{3} \biggr) \alpha G\bar\rho R \biggr] \xi_1</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4(1-x^2) - 2x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \biggl[ \frac{3n^2 }{2\pi \gamma G \bar\rho} - 2 \alpha \biggr] \xi_1</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 \, ,</math> |

where,

<math>~\mathfrak{F} \equiv \frac{3n^2 }{2\pi \gamma G \bar\rho} - 2 \alpha \, .</math>

Note that, once the value of the parameter, <math>~\mathfrak{F}</math>, has been determined for a given eigenvector, the square of the eigenfrequency will also be known via the inversion of this last expression. Specifically, in terms of <math>~\mathfrak{F}</math>,

|

<math>~n^2</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{2\pi \gamma G \bar\rho}{3} \biggl[ \mathfrak{F} + 2 \biggl(3-\frac{4}{\gamma}\biggr)\biggr]</math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~~ \frac{n^2}{4\pi G \bar\rho}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr)\gamma -\frac{4}{3} \, .</math> |

As a reminder, in these terms the inner boundary condition is

<math>~\xi_1^'\biggr|_{x = 0} = 0 \, .</math>

And the outer boundary condition becomes,

|

<math>~\xi_1^'</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\xi_1 \biggl( \frac{n^2 R}{\gamma g_0} - \alpha \biggr)</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\xi_1 \biggl[ \frac{3}{x}\biggl( \frac{n^2 }{4\pi \gamma G\bar\rho } \biggr) - 3 + \frac{4}{\gamma} \biggr]</math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~3\xi_1 \biggl\{ \frac{1}{x}\biggl[ \biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr) -\frac{4}{3\gamma} \biggr] - 1 + \frac{4}{3\gamma} \biggr\}</math> at <math>~x = 1 \, ,</math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow~~~~~\biggl[ \xi_1^' - \frac{\mathfrak{F} \xi_1}{2} \biggr]_{x=1}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~0 \, .</math> |

Sterne's General Solution

Sterne's Presentation

In what follows, as before, text presented in a green font has been taken verbatim from the paper by Sterne (1937). Sterne begins by writing the unknown eigenfunction as a power series expanded about the origin, specifically,

|

<math>~\xi_1</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\sum\limits_{0}^{\infty} a_k x^k \, ,</math> |

with, <math>~a_0 = 1</math>. It is found by substitution that the terms in odd powers of <math>~x</math> vanish, and that the coefficients of the even terms satisfy the recurrence formula,

|

<math>~a_{k+2}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~a_k \cdot \frac{k^2 + 5k - \mathfrak{F}}{(k+2)(k+5)} \, .</math> |

The wave equation and attending boundary conditions will all be satisfied if we choose <math>\mathfrak{F}</math> so as to make the series solution terminate with some term, say the <math>~2 j^\mathrm{th}</math> where <math>~j</math> is zero or any positive integer. This it will do [via the above recurrence relation] if,

<math>~\mathfrak{F} = 2j(2j+5) \, .</math>

The first few solutions are displayed in the following boxed-in image that has been extracted directly from §2 (p. 587) of Sterne (1937); to the right of Sterne's table, we have added a column that expressly records the value of the square of the normalized eigenfrequency that corresponds to each of Sterne's solutions.

|

Table extracted from T. E. Sterne (1937)

"Modes of Radial Oscillation"

Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 97, pp. 582 - © Royal Astronomical Society |

<math>~\frac{n^2}{4\pi G \bar\rho}</math> |

|---|---|

| <math>~\gamma - 4/3</math> | |

| <math>~2(5\gamma - 2)/3</math> | |

| <math>~7\gamma - 4/3</math> | |

| <math>~12\gamma - 4/3</math> |

Validity Check

Let's explicitly demonstrate that the first few eigenvectors derived by Sterne actually satisfy the governing adiabatic wave equation and the two boundary conditions.

Mode j = 0:

In this case,

<math>~\xi_1 = 1</math> and <math>~\mathfrak{F} = 0 \, .</math>

Hence,

<math>~\xi_1^' \equiv \frac{d\xi_1}{dx} = 0 \, ;</math> and <math>\xi_1^{' '} \equiv \frac{d^2\xi_1}{dx^2} = 0 \, .</math>

So, the adiabatic wave equation gives,

|

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~(1-x^2) (0) + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr](0) + (0)(1) \, ,</math> |

which properly sums to zero. Next, because <math>~\xi_1^' = 0</math> everywhere, we know that it is zero at the center of the configuration, which satisfies the inner boundary condition. But, via the outer boundary condition, this also means that the product, <math>~(\tfrac{1}{2} \mathfrak{F} \xi_1)</math> should be zero; which it is, because <math>~\mathfrak{F} = 0</math> for this mode.

Mode j = 1:

In this case, according to Sterne (1937),

<math>~\xi_1 = 1 - \frac{7}{5} x^2 \, ,</math> and <math>~\mathfrak{F} = 14 \, .</math>

Hence,

<math>~\xi_1^' = - \frac{14}{5} x \, ;</math> and <math>\xi_1^{' '} = - \frac{14}{5} \, .</math>

So, the adiabatic wave equation gives,

|

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- \frac{14}{5}(1-x^2) - \frac{14}{5}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr] + 14 \biggl( 1 - \frac{7}{5} x^2 \biggr) </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{14}{5}\biggl[- (1-x^2) - (4 - 6x^2 ) +5 - 7 x^2 \biggr] \, , </math> |

which properly sums to zero for all <math>~x</math>. Next, it is clear that the inner boundary condition is satisfied because,

<math>~\xi_1^'\biggr|_{x = 0} = - \frac{14}{5} (0)= 0 \, .</math>

And the expression for the outer boundary condition gives,

|

<math>~\biggl[ \xi_1^' - \frac{\mathfrak{F} \xi_1}{2} \biggr]_{x=1}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ -\biggl(\frac{14}{5} \biggr) x - 7 \biggl( 1 - \frac{7}{5}x^2 \biggr) \biggr]_{x=1} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ -\biggl(\frac{14}{5} \biggr) - 7 \biggl( 1 - \frac{7}{5} \biggr) \biggr] \, ,</math> |

which also properly sums to zero.

Mode j = 2:

In this case, according to Sterne (1937),

<math>~\xi_1 = 1 - \frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5} x^2 + \frac{3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 \, ,</math> and <math>~\mathfrak{F} = 2^2 \cdot 3^2 \, .</math>

Hence,

<math>~\xi_1^' = - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} x + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^3 \, ;</math> and <math>\xi_1^{' '} = - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^2 \, .</math>

So, the adiabatic wave equation gives,

|

<math>~(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } + \frac{1}{x}\biggl[4 - 6x^2 \biggr]\xi_1^' + \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ (1-x^2) \biggl[- \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^2 \biggr] </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + 2\biggl[2 - 3x^2 \biggr]\biggl[- \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^2\biggr] </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + 2^2 \cdot 3^2 \biggl[ 1 - \frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5} x^2 + \frac{3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 \biggr] </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} + \biggl[\frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} + \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} \biggr] x^2 - \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ - \frac{2^4\cdot 3^2}{5} +\biggl[ \frac{2^4 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} + \frac{2^3\cdot 3^3}{5} \biggr]x^2 - \frac{2^3 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 </math> |

|

|

|

<math>~ + 2^2 \cdot 3^2 - \frac{2^3\cdot 3^4}{5} x^2 + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^4 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~ \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5}\biggl[ -1 -4 + 5\biggr] + \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5\cdot 7}\biggl[33 + 7 + 44 + 42 - 2\cdot 3^2 \cdot 7\biggr] x^2 + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^3 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} \biggl[ 3 - 2 - 1\biggr] x^4 \, , </math> |

which properly sums to zero for all <math>~x</math>. Next, it is clear that the inner boundary condition is satisfied because,

<math>~\xi_1^'\biggr|_{x = 0} = - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} (0) + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} (0) = 0 \, .</math>

And the expression for the outer boundary condition gives,

|

<math>~\biggl[ \xi_1^' - \frac{\mathfrak{F} \xi_1}{2} \biggr]_{x=1}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ - \frac{2^2\cdot 3^2}{5} x + \frac{2^2 \cdot 3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^3 - 2\cdot 3^2 \biggl( 1 - \frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5} x^2 + \frac{3^2 \cdot 11}{5 \cdot 7} x^4 \biggr) \biggr]_{x=1} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{2\cdot 3^2}{5\cdot 7}\biggl[ -14 + 22 - \biggl( 35 - 126 + 99 \biggr) \biggr] \, ,</math> |

which also properly sums to zero.

Properties of Eigenfunction Solutions

Stability

The Adiabatic Wave Equation that defines this eigenvalue problem has been derived from the fundamental set of nonlinear Principal Governing Equations by assuming that, for example, the radial position, <math>~r(m,t)</math>, at any time, <math>~t</math>, and of each mass shell throughout our spherical configuration can be described by the expression,

<math>~r(m,t) = r_0(m) [ 1 + x(m) e^{i\omega t} ] \, ,</math>

where, the fractional displacement, <math>~|x| \ll 1</math>. Switching to Sterne's variable notation, this should be written as,

<math>~\xi(x,t) = \xi_0(x) [ 1 + A\xi_1(x) e^{i n t} ] \, ,</math>

with the presumption that the coefficient, <math>~|A| \ll 1</math>, and the understanding that, in Sterne's presentation, the variable, <math>~x</math>, is used to identify individual mass shells. Specifically, given <math>~R</math> and <math>~\bar\rho</math>,

<math>~m \equiv M_r = \frac{4}{3}\pi \xi_0^3 \bar\rho = \frac{4}{3}\pi (R x)^3 \bar\rho </math> <math>~\Rightarrow</math> <math>~x = \biggl( \frac{3m}{4\pi R^3 \bar\rho} \biggr)^{1/3} \, .</math>

Sterne's general solution of this eigenvalue problem describes mathematically how a self-gravitating, uniform-density configuration will vibrate if perturbed away from its equilibrium state; the oscillatory behavior associated with each pure radial mode, <math>~j</math> — among an infinite number of possible modes — is fully defined by the polynomial expression for the eigenvector, <math>~\xi_1(x)</math>, and the corresponding value of the square of the eigenfrequency, <math>~n^2</math>.

If, for any mode, <math>~j</math>, the square of the derived eigenfrequency, <math>~n^2</math>, is positive, then the eigenfrequency itself will be a real number — specifically,

<math>~n = \pm \sqrt{|n^2|} \, .</math>

As a result, the radial location of every mass shell will vary sinusoidally in time according to the expression,

<math>~\frac{\xi(x,t)}{\xi_0} - 1 \propto e^{\pm i \sqrt{|n^2|} t} \, .</math>

If, on the other hand, <math>~n^2</math>, is negative, then the eigenfrequency will be an imaginary number — specifically,

<math>~n = \pm i \sqrt{|n^2|} \, .</math>

As a result, the radial location of every mass shell will grow (or damp) exponentially in time according to the expression,

<math>~\frac{\xi(x,t)}{\xi_0} - 1 \propto e^{\pm \sqrt{|n^2|} t} \, .</math>

This latter condition is the mark of a dynamically unstable system. It is in this manner that the solution to an eigenvalue problem can provide critical information regarding the relative stability of equilibrium configurations.

For any given mode number, <math>~j</math>, then, the critical configuration separating stable from unstable systems occurs when the dimensionless eigenfrequency is zero. Therefore, the critical state occurs when,

|

<math>~0 = \frac{n_\mathrm{crit}^2}{4\pi G \bar\rho}</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr)\gamma_\mathrm{crit} -\frac{4}{3} </math> |

|

<math>~\Rightarrow ~~~~~ \gamma_\mathrm{crit}(j)</math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{4}{3}\biggl(1 + \frac{\mathfrak{F}}{6} \biggr)^{-1} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{4}{3}\biggl[1 + \frac{2j(2j+5)}{6} \biggr]^{-1} </math> |

|

|

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\frac{4}{3 + j(2j+5)} \, . </math> |

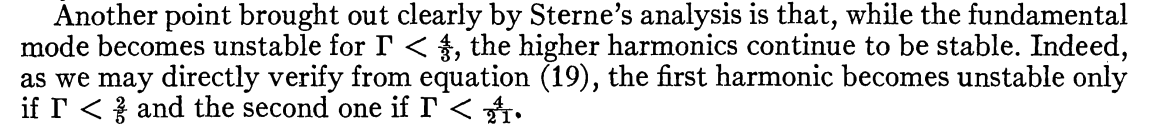

The plot titled, "Critical Adiabatic Index," that is presented above shows graphically how <math>~\gamma_\mathrm{crit}</math> varies with mode number over the range of mode numbers, <math>~0 \le j \le 11</math>. All modes are stable as long as <math>~\gamma > 4/3</math>. As the adiabatic index is decreased below this value, the lowest order mode, <math>~j = 0</math>, becomes unstable, first; then successively higher order modes become unstable at smaller and smaller values of the index. A very similar explanation and enunciation of Sterne's derived results regarding the stability of uniform-density spheres appears on p. 338 of the paper by P. Ledoux (1946) titled, On the Dynamical Stability of Stars. The relevant paragraph from Ledoux's paper is reprinted as a boxed-in digital image in the following table:

|

Paragraph extracted† from p. 338 of P. Ledoux (1946)

"On the Dynamical Stability of Stars"

The Astrophysical Journal, vol. 104, pp. 333 - 346 © American Astronomical Society |

|---|

|

†Our function, <math>~\gamma_\mathrm{crit}(j)</math>, is effectively the expression to which Ledoux is referring when he says, "… directly verify from equation (19) …" |

Numerical Integration

In order to gain a more complete understanding of this type of modal analysis, let's attempt to obtain various eigenvectors by numerically integrating the governing LAWE from the center of the system, outward to the surface. This will be done in a manner similar to our numerical study of radial oscillations in zero-zero bipolytropes. Following our above review of Sterne's presentation, the relevant LAWE is,

|

<math>~x(1-x^2) \xi_1^{ ' ' } </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~- (4 - 6x^2 )\xi_1^' - x \mathfrak{F} \xi_1 \, ,</math> |

where,

<math>~\mathfrak{F} \equiv \frac{\sigma_c^2}{\gamma} - 2 \alpha = \frac{\sigma_c^2 + 8}{\gamma} - 6\, ,</math> and, <math>~\sigma_c^2 \equiv \frac{3n^2 }{2\pi G \rho_c} \, .</math>

Following precisely the same logic as has been laid out in our separate discussion, if we set the central value of the eigenfunction to <math>~\xi_0</math>, then the eigenfunction's value at the first zone (distance <math>~\Delta</math>) away from the center will be,

|

<math>~ \xi_+ </math> |

<math>~=</math> |

<math>~\biggl[ 1 - \frac{\Delta^2 \mathfrak{F}}{2} \biggr] \xi_0 \, . </math> |

While, for each successive coordinate location, <math>~a = x</math>, in the range, <math>~0 < x < 1</math>, we will use the general expression, namely,

|

<math>~ \Rightarrow~~~\xi_+ </math> |

<math>~\approx</math> |

<math>~\frac{[4a (1 - a^2) - 2\Delta^2 a \mathfrak{F} ]\xi_a + [ \Delta( 4 - 6a^2 ) - 2a (1 - a^2)] \xi_- }{[2a (1 - a^2) + \Delta( 4 - 6a^2 ) ] } \, . </math> |

|

|---|

|

© 2014 - 2021 by Joel E. Tohline |